Reviews of Past Gigs

Greg Abate and the Craig Milverton Trio

Friday 12 July 2019 Progress Theatre, Reading

Greg Abate, alto saxophone, flute, composer, leader | Craig Milverton, piano | Adam King, double bass | Nick Millward, drums

Jazz at Progress completed the summer season with an intimate evening’s music from Rhode Islander Greg Abate, a regular UK visitor.

With a packed schedule of British dates, including a visit to a well-known Sussex coastal city, he suggested they might start with “I ‘Hove’ You” (Cole Porter’s “I Love You”), but in fact launched into an up-tempo “What is This Thing Called Love”. The dynamic alto solo included (among other quotes), a snatch of Dameron’s contrafact “Hot House” (a tune Greg has recorded more than once and clearly enjoys).

Switching to flute (apparently an advance request from a local flute player – sadly not able to attend – prompting Greg to relate he often receives requests for specific instruments in his portfolio from fans who then can’t be there) we next heard Joe Henderson’s popular bossa nova “Recorda-Me”, with sparkling solos from all the band.

Having already (musically) referenced Tadd Dameron, the band followed with his composition “Afternoon in Paris”, starting with a trio (alto, bass, drums), then joined by piano. Pianist Craig Milverton is often in demand to accompany visiting US musicians, as well as being busy with many of his own projects.

“Contemplation”, an Abate minor blues composition, again showed his versatility, and command of flute. Piano, bass, and drums solos followed. Drummer Nick Millward is said to have based his approach on Buddy Rich. As well as vocalist in his own band, Nick has a distinguished career with traditional bands including those of Kenny Ball Jr. and Terry Lightfoot. This evening he demonstrated his ability to play superbly in any genre.

Returning to alto, the second standard of the evening, “Moonlight in Vermont” began with an unaccompanied statement on saxophone, before the band joined. This composition, like several of the evening’s selections, is featured on Greg’s album Kindred Spirits with Phil Woods. This was a very rhythmic interpretation, the band moving into double time (and then double-double), with a thoughtful bass solo from Adam King, 2015 Young Jazz Musician, he studied at Middlesex University, and cites Jaco Pistorius as his inspiration for switching to bass from his first choice, alto saxophone.

The first set closed with a fast version of “Star Eyes”, a favourite with jazz soloists since the bop era. After solos the band moved on to 8 bar exchanges. Before closing the set, the Progress audience were intrigued with what may be a Greg Abate trademark: short musical ‘duets’ or ‘conversations’ with each of the trio, where Greg played a short phrase, and the other ‘replied’.

After the break (during which Greg continued the relaxed feeling of the evening, by freely chatting with audience members in the lounge), the band went to a fast “Yardbird Suite”.

At a contrasting tempo, the second ballad of the evening, “In a Sentimental Mood” again presented Greg’s alto in an expressive interpretation, deploying varied articulations, dynamics, and the full range of the instrument. Craig Milverton took the middle eight on the opening theme, unhurried and with occasional ‘outside’ harmonic colour.

Another standard, reminiscent of the Charlie Parker repertoire, “I’ll Remember April” followed, in a very fast reading. Alternating latin and swing rhythms were enhanced by the fine drumming of Nick Millward.

The last flute feature of the concert, “Lullaby of Birdland” was taken at a steady tempo, but with plenty of fluent double time in the flute solo. Craig’s piano solo included some ‘locked hands’ chordal playing (a nod to the composer’s style?), before a bass improvisation with Craig inserting a “walking bass line” on piano.

After selections from some of the most celebrated jazz composers, what could be more apt than Monk’s “`Round Midnight”? Quotes, they say, are a neglected feature of the improviser’s skill; a reference to the preceding theme in the alto solo illustrated this nicely.

Leaving the audience wanting more, the band finished on a high note (altissimo C on alto?) and at breakneck speed: “Donna Lee”, conventionally taken at a fast tempo, but here at a lick that defeated one audience member’s new BPM (beats per minute) app designed to pick up the metronome marking!

Sincere thanks to Greg Abate and all the Craig Milverton trio for a superb evening, and, as ever, to the Progress Theatre people, Hickies of Reading for the piano, and all the Jazz in Reading team.

Review posted here by kind permission of Clive Downs

Photo by Colin Swain Photography

Paz

Friday 21 June 2019 Progress Theatre, Reading

Les Cirkel drums, Rob Statham bass, Geoff Castle keyboards, synthesizer, Chris Fletcher percussion, Matt Wates alto saxophone, Dominic Grant guitar

What better way to celebrate the Summer Solstice than in the company of Paz and their high octane mix of jazz improvisations, earthy funk and the irresistible rhythms of South America and the Caribbean – Fusion at its timeless best!

The band emerged nearly fifty years ago as the brainchild of the late Dick Crouch, a characterful individual with a remarkable gift for composition within the Fusion genre. His writing remains at the heart of the band’s repertoire. With a day-job in the Transcription Department of the BBC, his Shepherd’s Bush office became an open-house for like minded musicians, who took full advantage of the subsidised meals available in the canteen. The amiable Geoff Castle, current leader of the band who joined its ranks in 1974, describes Dick Crouch as a vibes player who set up his instrument at gigs but rarely played a note, preferring to strike a languid pose and soak up the music from within a cloud of Gauloises’ tobacco haze – what a wonderful image that conjures in our modern world of clean-cut stage presentation!

Drummer Les Cirkel has been with Paz from its formation, though he claims to have only been seven years old at the time; Chris Fletcher joined ‘after the war’, but fails to admit which one; Rob Statham and Matt Wates have clocked up respectively nearly forty and fast approaching thirty years, while Dominic Grant, is the ‘juvenile’ of the organisation with a mere twelve months service. It’s little wonder that these guys convey a slight air of ‘been there, done that’, for they are seasoned professionals with countless gigs to their credit, who have clocked up thousands of hours in the recording, TV and film studios and played with the giants of the entertainment business.

‘For Art’ immediately reveals the strength of Dick Crouch’s writing. Originals are so often no more than flimsy hooks on which to hang a string of solos. That’s not so here. It’s beautifully formed with a distinct shape, a logical structure and intensely exciting; a hallmark of quality that sets the standard flying for the evening.

Dominic Grant makes full use of his wa-wa pedal to set the groove on ‘One Hundred’ (a title which should be proclaimed a la Sid Waddell, the famed darts commentator), and Matt Wates soars into flight with his gorgeous alto as the rhythms, firmly anchored by Rob Statham’s bass guitar, build layer upon layer in the background.

Geoff Castle takes the writing credits for ‘Latinesque’, a breathtaking Samba with a subtle hint of melancholy courtesy of Chris Fletcher’s ingenious percussion effects. Castle was also responsible for ‘Citroen Presse’, a title which accurately depicts the sad fate of his much loved Citroen 2CV. Far from being a car crash this number swings like the clappers.

‘Making Smiles’ and ‘Forever’, the first a full-on tsunami of sound, contrasting textures and rhythm, the second a bright, sparkling samba, completed the first set in dedication to the great alto saxophonist Ray Warleigh and his long tenure with Paz in its earlier days,

‘Looking Inside’ opens the second set, a slow, wistful number and the title track from Paz’s best selling album produced by Miles Davis associate Paul Buckmaster. ‘Bags’, a dedication to Milt Jackson, keeps everyone on their toes. Its constant shifts in time and rhythm, inspire brilliant solos from Matt Wates and Geoff Castle, and the whole thing builds to a thrilling climax between Les Cirkel’s drums and Chris Fletcher’s congas.

‘James the First’, a dedication to Dick Crouch’s first-born child, brings the sound of steel pans (one of many intriguing sounds emanating from Geoff Castle’s Moog synthesizer) and the gaiety and fresh breezes of the Caribbean to the stage. An absolute delight!

‘AC/DC’ proved to be such a hit on the London disco scene in the 1980s that the record company couldn’t keep pace with demand and no wonder – a fantastic piece that’s lost none of its power or appeal in the intervening years. ‘Laying Eggs’, on the other hand, with the snappy guitar of Dominic Grant to the fore, lays down a solid groove and explores the darker territory of heavy-funk.

Geoff Castle’s ‘Variation on Creation’, can best be described as a calypso tear-up, with everyone stoking the boiler to round off a brilliant evening in great style. Except of course, the gig can’t possibly end here; rather than provoke a riot the band plays out to the cool tones of ‘Harmonique’ followed by a quick-fire reprise of ‘AC/DC’.

Fusion is alive and kicking in the safe hands of the gentlemen of Paz and long may it continue to be so!

As ever, thanks to Martin Noble for the excellent quality of sound and lighting, and to the Progress Front of House team for their warm hospitality’

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

The Bobby Hutcherson Project: Orphy Robinson MBE Quintet

Friday 17 May, Progress Theatre, Reading

Robert Mitchell keyboard, Tony Kofi alto saxophone, Rod Youngs drums, Orphy Robinson MBE vibraphone & marimba, Dudley Phillips bass.

As many high-profile promoters and recording producers will reluctantly testify, bringing together a ‘dream package’ of star jazz performers is no guarantee of either artistic or commercial success. All too often what seemed like a great idea on paper ends up with underwhelming performances when enlarged egos and arguments about billing get in the way of making music. Not so when Orphy Robinson was asked to put together a band to pay tribute to the great vibes player Bobby Hutcherson who died on 15 August 2016 age seventy-five.

Such was the respect for Bobby and love of his music that not only were all the musicians Orphy approached eager to play, more importantly, each one was available for the date in September 2016. Voted ‘Live Experience of the Year’ in the 2017 Jazz FM Awards, the concert gave birth to the ‘Bobby Hutcherson Project’ under the direction of Orphy Robinson MBE, which received a rapturous reception from the sell-out audience when it took to the stage of the Progress Theatre on Friday 17 May. What the tiny theatre lacked in numbers – it only has 96 seats – it more than made up for in volume and atmosphere, prompting Orphy to remark, ‘This is like Wembley Stadium!’

In the early 1960s Hutcherson took, what was then and still remains an unfashionable instrument, the vibraphone, to the cutting-edge of jazz innovation. His impeccable mastery of the instrument and personal sound was matched by his energy, gift for invention and unique sense of space and freedom. He recorded prolifically as a leader, while his versatility and ability to bring something special to any situation meant that he was always on call as a sideman. He also made two film appearances – as a bandleader in ‘They Shoot Horses Don’t They?’ and a featured role alongside Dexter Gordon in ‘Round Midnight’.

‘Knucklebeam’, an Eddie Marshall composition and the title track of a 1977 Blue Note album, might have been more aptly titled ‘Knuckle Ride’; an exhilarating outing that tested the mettle of each band member and left the audience in a state of breathless excitement. What an opening number, and a mere taste of what was to come!

‘So Far, So Good’, penned by James Leary and also from the ‘Knucklebeam’ album, cooled the temperature and allowed the band to stretch out in a more relaxed groove. Tony Kofi’s passionate and free-flowing expression on alto saxophone was like a gift from heaven. The astonishing Robert Mitchell, familiar as the pianist and MD for the recent ‘BBC Four celebrates Jazz 625 For One Night Only’, took the keyboard apart in every sense of the word. He uses both hands and sometimes cross-hands with equal force to build solos of unbelievable depth and complexity. Urged on by his fellow players and the awe-struck audience, his playing became ever more audacious as the evening progressed. Orphy Robinson’s solos on the other hand, are visually stunning and unfold as if the pages of a book, with a clear narrative thread and a reflective space between each chapter. Underpinned by the brilliant rhythm team of Dudley Phillips on bass and drummer Rod Youngs, this is a band of truly world-class stature.

The hard-swinging ‘Tahiti’, paid tribute to Milt Jackson, a profound influence on both Hutcherson and Robinson, before the band rounded-off the first set with a sensational ‘Recorda-Me (Remember Me)’ by giant of the tenor saxophone Joe Henderson, featuring the mellow-sounds of Orphy Robinson’s marimba – his remarkable Xylosynth combines the characteristics of vibes and marimba in one instrument!

The second set opened with the Fender/Rhodes sounds of Robert Mitchell’s keyboard setting a dreamlike atmosphere for ‘Montara’, Hutcherson’s title track from the 1975 album, described by one contemporary ‘as capturing the spirit of those times like no other’. A soulful fusion of gentle latin rhythms and the solid groove of Dudley Phillips’ electric bass, one could simply immerse oneself in the gorgeous caress of Orphy’s marimba and the plaintive saxophone of Tony Kofi.

Drummer Rod Youngs used his hi-hat cymbals to ignite ‘Stick Up’, a number in which the light and shade of Orphy’s vibraphone contrasted beautifully with the edge-of-your-seat excitement of Robert Mitchell’s piano solo.

The spikey ‘Gazzelloni’, celebrated Bobby Hutcherson’s role as a sideman on Eric Dolphy’s Blue Note album ‘Out to Lunch’ from 1964. Regarded at the time as being on the outer limit of free-jazz expression, it’s no less challenging today. It morphed imperceptivity into the gentler strains of ‘Hat and Beard’ also from Dolphy’s groundbreaking album. A highlight – Rod Youngs’ hand-drumming as the culmination of his drum solo and a sublime moment of silence before the band came back in for the coda. Pure magic!

An irresistible summons to have a great time ‘Ummh’ set hands clapping to the groove and brought an enthralling concert to a fitting close way beyond the official ending time of 10 o’clock. The enduring spirit and rich musical legacy of Bobby Hutcherson rests safely in the hands of Orphy Robinson MBE and the Bobby Hutcherson Project.

Thanks should also be extended to Martin Noble sound-and-light-man-extraordinaire and the Progress House Team whose warm hospitality and attention to detail ensured that the evening ran so smoothly.

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

Henry Lowther’s Still Waters

Friday 12 April, Progress Theatre, Reading

Henry Lowther trumpet & flugelhorn | Pete Hurt tenor saxophone | Barry Green keyboard | Dave Green bass | Paul Clarvis drums

‘National treasures’ seems to be a rather twee epithet to describe two musicians who’ve each graced the rough and tumble of the professional jazz scene for the past fifty-plus years, but I can’t think of anything else more suitable or more deserving. Henry Lowther and Dave Green are NATIONAL TREASURES. The fact that they are back together and touring with Still Waters after an interval of twenty years, is not only to be celebrated but should be shouted from the roof tops.

The evening opened with ‘Can’t Believe, Won’t Believe’, the title track of the band’s latest album; a reflection on the scepticism of our present times and a challenge to any listeners who might doubt that the lyrical beauty of Lowther’s composition could fit so perfectly with the turbulent drumming of Paul Clarvis One might have expected gentle brushwork and subdued cymbals. Not so! The ever-shifting rhythmic patterns and rich variety of sounds he drew from his minimalist kit emphasized that the emotional undercurrents of still waters do indeed run deep.

The Latin-tinged ‘TL’ paid tribute to the late Tony Levin and carried all the force of the musician who Tubby Hayes regarded as being ‘his ideal drummer’.

According to an astrology site that I consulted Capricorn is the sign that ‘represents time and responsibility … and its representatives are serious by nature with an inner state of independence’. Whether these characteristics fit Pete Hurt, who was born under the sign, I wouldn’t like to say, but one thing is for sure – he is a writer and tenor saxophonist of rare quality as the intense excitement of ‘Capricorn’ more than demonstrated.

‘Amber’, a dedication to Barry Green’s now two-and-half-year-old daughter, presented the band at its most expressive, with Lowther on flugelhorn and the proud father creating celestial sounds with his elegant touch at the keyboard. Dave Green, rightfully known as the ‘Rolls Royce of bass players’ completed the atmosphere of total sublimity.

Henry Lowther’s droll announcements proved to be a highlight of the evening. None more so than in his explanation of how the next number acquired it intriguing title. Though Its challenging rhythms seemed familiar, he couldn’t think from where. The penny only dropped when he remembered playing at a Moroccan jazz festival with a group from the Gnawan dynasty of musicians. His new tune bore their influence, hence the title ‘Something Like…’ It brought the first set to an exhilarating close.

The second set opened with the only standard of the evening, ‘Too Young to Go Steady’, a product of the Jimmy McHugh/Harold Adamson writing partnership, recorded by Nat King Cole in 1956 and by John Coltrane on his ‘Ballads’ album of 1962. No matter the note of caution in the title, this fulfilled all the romantic promise of a walk in a park, featuring the gorgeous tenor saxophone of Pete Hurt and an extended bass solo of near-singing perfection from Dave Green.

Much as Henry Lowther clearly loves a challenge, he must have thought ‘You must be having a laugh’ when the organisers of a Finnish jazz festival asked him to compose a piece of music to fit the palindrome ‘Saippuakauppias’ (soap vendor). To their astonishment, and ours, he met the challenge with complete success, though he did admit that the rigid structure of the piece would relax part way through ‘otherwise it might get boring.’ As if it could.

‘Golovec’ again bore the imprint of Lowther’s wide musical travels with its haunting evocation of the Slovenian forest. ‘White Dwarf’, on the other hand took us into quite different territory, with a remarkable ‘free’ section in which Henry Lowther and Paul Clarvis spurred each other on to ever-more-exciting feats of invention.

The evening closed on a note of reflection with ‘For Pete’, Pete Hurt’s elegiac dedication to the late Pete Saberton, the band’s first pianist.

Along with our thanks to the Progress House Team for their warm hospitality and the excellent quality of sound and lighting, we should also acknowledge the enlightened support of the Arts Council in helping Henry Lowther’s Still Waters take to the road on a nineteen-date tour of the UK. Let’s hope that it provides the impetus for future recordings and continued success.

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

A Portrait of Cannonball

Friday 22 February, Progress Theatre, Reading

Tony Kofi alto saxophone | Byron Wallen trumpet | Alex Webb piano | Andy Cleyndert bass | Alfonso Vitale drums | Deelee Dubé guest vocalist

Julian Edwin Adderley was born in Tampa, Florida on 15 September 1928. His voracious appetite earned him the sobriquet ‘Cannibal’. That it later evolved into the much more acceptable ‘Cannonball’ proved an absolute gift for the copywriters who devised his early album titles. What could be better than ‘Cannonball’s Sharpshooters’ for an attention-grabbing banner? ‘Spontaneous Combustion’ perhaps? Cannonball’s debut album for the Savoy label in 1955 announced his arrival on the New York jazz scene as a player of immense vitality and invention. He made people sit up and listen, but above all, to use Tony Kofi’s words from his beautifully poetic introduction to ‘A Portrait of Cannonball’, he made them smile.

It was the warmth of Cannonball’s humanity that endeared him to millions of fans across the world, and which instantly communicated itself with the Progress audience. Alex Webb lit the fuse to ignite ‘Bohemia After Dark’, and with sparks flying between the rhythm section and the tight front-line of Tony Kofi and Byron Wallen, it was clear that this promised to be an evening to remember.

Like Cannonball, Tony Kofi and Byron Wallen are absolute masters of the blues, as they clearly demonstrated on ‘Thing Are Getting Better’. A beautifully paced mid-tempo number, firmly anchored by Andy Cleyndert’s rich-toned bass lines and the sensitive pulse of Alfonso Vitale’s drumming, it allowed everyone to relax and really stretch out with their solos

‘Nardis’ explored darker territory. Wallen’s growling, ‘stepping-on-eggshells’ trumpet, the pure tone of Kofi’s alto and Alex Webb’s Spanish tinged piano combined to fully express the brooding qualities of the Miles Davis composition.

Alex Webb’s excellent narration linked each number within the wider context of Cannonball’s burgeoning career. We soon arrived at 1960 and ‘Del Sasser’, an earthy Sam Jones original from ‘Them Dirty Blues’, Cannonball’s landmark album for Riverside records. If the pots had been simmering up to this moment in the evening, Andy Cleyndert’s magnificent bass solo brought them fully to boiling point!

Rapturous applause greeted the arrival of guest vocalist Deelee Dubé, to evoke Cannonball’s 1961 collaboration with Nancy Wilson, a great singer who sadly died in December 2018. Ms Dubé, the first British recipient of the Sarah Vaughan International Jazz Vocal Award, has a voice of the purest gold. She lit up the stage as she launched into ‘Happy Talk’, with Kofi and Wallen busily ‘chattering’ away in their own musical conversation by way of accompaniment. ‘A Sleepin’ Bee’ by Harold Arlen and Truman Capote, revealed the full depth, range, crystal-clear diction and swing of Ms Dube’s beautiful voice. Absolute magic!

British born Victor Feldman, a brilliantly rounded musician who achieved that rare distinction of ‘making it’ in the States, contributed ‘Azule Serape’ (Blue Shawl) to Cannonball’s ‘At the Lighthouse’ album of 1961. Its open-spaced, Latin-tinged swing provided the perfect launchpad for a dazzling drum solo from Alfonso Vitale and brought an exhilarating first set to a close.

The elegant piano lines of Alex Webb set the second half in motion with Duke Pearson’s ‘Jeanine’, a dreamy, beautifully melodic number, whose precision and logic opened up endless possibilities for improvisation. On the other hand, ‘Sack O’ Woe’, another classic from ‘At the Lighthouse’, and taken a little faster than the original recording, presented the rhythm section at its most soulful and the front-line of Kofi and Wallen at their most exuberant. What fantastically expressive players they are!

Deelee Dubé’s return to the stage not only brought thunderous applause, but truly affirmed her place as a ‘brilliant new voice’ on the UK jazz scene. She negotiated the tricky rhythms of Frank Loesser’s ‘Will I Marry’ with absolute aplomb, captured the tender emotions of ‘The Masquerade is Over’ to perfection, aided by Byron Wallen’s wonderfully expressive obbligato trumpet, both muted and open, and delivered ‘Big City’ as a showstopping belter with the support of the band in full cry. Great!

‘Walk Tall’, a Joe Zawinul number from the 1967 album ’74 Miles Away’ and also the title of Cannonball’s biography, brought us into the final phase of his career which came to a much-too-early close with his death age 46 on 8 August 1975. It also provided a fitting background to the remarkable achievements, listed by Tony Kofi, which form Cannonball’s enduring legacy – a legacy which extends way beyond music to the heart of African-American identity through his support for Civil Rights and education projects.

After the gentle Latin breeze of ‘Saudade’, Deelee Dubé returned to the stage for the grand finale – what else but ‘Work Song’. If anything defines Cannonball, it’s this number from the pen of cornet-playing-brother Nat – earthy, blues-soaked and overflowing with the power of the human spirit!

To borrow a phrase from another commentator, ‘A Portrait of Cannonball was a blast!’ and in the words of one Progress regular, ‘It was the best gig that I’ve seen at Progress.’ I don’t think anyone could argue with either judgment.

Thanks are due to Hickies Music Store of Friar Street, Reading for the hire of an excellent piano and as ever to the Progress house team for their hospitality and the excellent quality of sound and lighting.

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

Gilad Atzmon & The Orient House Ensemble “Spirit of Trane” | January 2019

Friday 18 January, Progress Theatre, Reading

Gilad Atzmon soprano, alto & tenor saxophones | Ross Stanley piano | Yaron Stavi double bass, | Enzo Zirilli drums

Their ears assailed by what seemed like an obsessive twenty-three-minute solo outing of ‘My Favourite Things’ on a strange high-pitched serpent-like instrument, the soprano saxophone, large chunks of the audience voted with their feet and beat a hasty retreat from the Gaumont State Kilburn on the opening night of John Coltrane’s first, and only, visit to Britain on 11th November 1961. ‘WHATHAPPENED!’ (sic) screamed the Melody Maker headline. It left the paper’s Bob Dawbarn, ‘baffled, bothered and bewildered’. The critical debate continued unabated in the jazz press with Benny Green, saxophonist, writer, broadcaster and general know-all, who incidentally didn’t attend the concert (or any that followed in Birmingham, Glasgow or Newcastle for that matter) adding his two-penny-worth by declaring that ‘Coltrane threatens to upset the entire jazz conception’. And thus, John Coltrane added his name to those of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, judged respectively to be ‘too loud’ and ‘too exotic’ when they first played on these shores; in Coltrane’s case he was ‘too loud’, ‘too exotic’ and ‘too long’.

With this occasion in mind, ‘Are you ready to be challenged?’ seemed a fair question for Gilad Atzmon to ask in his inimitable and uncompromising manner as he set the scene for a two-hour concert inspired by the ‘Spirit of Trane’; have we Brits become more attuned to the sound and emotional impact of John Coltrane over the passage of nearly sixty years?

‘Yes!’ came the resounding response from the sell-out Progress audience, in perhaps the nearest experience we shall ever have of listening ‘live’ to John Coltrane. True, there were no marathon solos, or any of the ugly, grating sounds from the latter days of Coltrane’s much-too-short career, and he did break us in gently with the beautiful ‘In A Sentimental Mood’ from the 1962 collaboration with Duke Ellington, and the Latin breeze of ‘Invitation’, but come ‘Moment’s Notice’ he hit the ground running and it was as much as we could do from then on to keep up.

It wasn’t so much the ferocious tempo that was so impressive, but rather the sheer momentum of Atzmon’s playing. Fueled by Enzo Zirilli’s drums, the rock-steady bass of Yaron Stavi and Ross Stanley’s timely contributions at the keyboard, the notes flowed from Gilad’s tenor in a torrent so characteristic of Coltrane and which prompted the writer Ira Gitler to coin the phrase ‘sheets of sound’; each as hard-edged as steel and filled with a haunting melancholy. And yet, however complex the improvisation became it never lost touch with the original theme, suggesting that Coltrane was actually a far greater ‘tunesmith’ than he was ever credited for.

The sublime ballad ‘Say It Is’, in which bassist Yaron Stavi demonstrated that the art of playing a melodic walking bass solo is still alive and well, provided a welcome breathing space before the band launched into another maelstrom of sound. And Gilad set yet another challenge, or maybe he was simply playing mesmerizing tricks with our aural senses. What was he playing? ‘Scarborough Fair’? ‘My Favourite Things’? Ross Stanley kindly resolved the conundrum in a brief interval chat and confirmed that ‘it was both!’ No matter, the effect was enthralling!

‘Big Nick’, a catchy dedication to ‘Big’ Nick Nicholas, the tenor saxophonist alongside whom Coltrane sat in the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band, and another title from the Ellington collaboration, brought the first set to a light-hearted conclusion.

The second set opened with ‘Impressions’ and ‘Naima’, the name of Coltrane’s then wife, and each bore the imprint of his fascination for Far Eastern philosophy and mysticism. Gilad switched from soprano to alto for ‘Giant Steps’ with the assurance that he would take the tune at a more leisurely waltz time than the breakneck speed of Coltrane’s original recording. He failed … and matched the original in every detail in a breathtaking display of virtuosity.

‘What’s New’ brought another change of instrument. Gilad switched to his tenor, a beautiful product of English craftmanship as he explained, made in 1926. Coincidence or what? 1926 was the year of John Coltrane’s birth. It provided the perfect vehicle for Bob Haggart’s tender ballad more often associated with trumpet players than saxophonists.

I would guess that Gilad’s original composition ‘The Burning Bush’ is open to many interpretations, but for me it stood as a series of lamentations, expressing a sense of near-despair, etched even more deeply by his use of vocal cries to separate each section and Enzo Zirilli’s emotionally charged drum solo and percussive effects. Listening to it was an extraordinarily moving experience.

What better way to round off the evening than ‘Mr. P.C.’; not a description of Gilad Atzmon, but a dedication to bassist Paul Chambers, Coltrane’s colleague in the Miles Davis Quintet and countless other recordings including the monumental ‘Giant Steps’. Nat Hentoff was of course writing about John Coltrane in his sleeve notes to the album. However, his closing sentence could equally apply to Gilad Atzmon:

‘He asks so much of himself that he can thereby bring a great deal to the listener who is also willing to try relatively unexplored territory with him.’

All praise to Gilad Atzmon and the Orient House Ensemble and to everyone at the Progress Theatre for hosting a truly memorable event; a wonderful evocation of the spirit and enduring legacy of John Coltrane.

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Colin Swain Photography

Jean Toussaint Sextet “Brother Raymond Tour” | December 2018

Friday 14 December, Progress Theatre, Reading

Jean Toussaint tenor saxophone, composer, leader | Byron Wallen trumpet, composer, percussion | Tom Dunnett trombone | Daniel Casimir double bass, composer | Andrew McCormack piano | Shane Forbes drums

Just when you thought you could escape Brexit for a few hours at a jazz concert, an ex-Jazz Messenger reminds you with a composition prompted by it! Yes, it was Jean Toussaint, promising to warm up the capacity Progress audience on a freezing night, as the Sextet kicked off what was billed as the last stop on their UK (plus brief diversion to Paris) “Brother Raymond Tour”.

With the last concert of the year in Jazz at Progress’ varied 2018 – 2019 season, what had been planned as a quintet, evolved to a sextet with the late addition of Birmingham Conservatoire graduate Tom Dunnett on trombone. Promoting his album, the “Jean Toussaint Allstar 6tet: Brother Raymond”, the now London-resident former Jazz Messenger presented a programme of original compositions (an encore one exception), mainly drawn from the CD.

Jazz musicians like giving their compositions cryptic titles (sometimes derived from foreign languages); Mr Toussaint explained “Amabo” was dedicated to Barack Obama, (spelt backwards). Fortuitously, he discovered this means ‘I shall love’ in Latin. Indeed the opener, starting with contrapuntal lines from the horns, had a strong latin (-american) feel. New York based Andrew McCormack provided a percussive piano solo.

First of the evening’s compositions from other band members, “Gate Keeper”, again with latin rhythms, by composer and trumpeter Byron Wallen – a late change to the line-up – was built on a simple two note repeated rhythmic figure.

Shane Forbes (2009 winner of The Musicians Company Young Musician Award) was in the spotlight for a drum feature at the start of the following number, second of the evening from the album, “Doc”, composed by Jean Toussaint, and dedicated to the band leader’s cousin.

Hoping to assuage any referendum-induced negativity, Jean Toussaint introduced his next composition, “Major Changes”; based solely on major chords, this is a bright, up-tempo piece with a calypso pulse.

Opening the second set on a slow ballad, “Milena”, Jean Toussaint noted the number was dedicated to his girlfriend, the inspiration for much of his music. As with all the original material in the concert, the piece has a carefully planned structure with ensemble passages, solos with rhythm section, or horn accompaniment, and interludes.

Next we heard the CD title track, “Brother Raymond”, a medium-tempo composition with rich voicings from the front line. As well as instrumental ensembles, the horn players sang a wordless vocal riff over a bass and drum duet.

Another Birmingham Conservatoire graduate (and 2016 Young Jazz Musician Award winner), bassist Daniel Casimir wrote the beautiful “The Missing of Sleep” for his daughter born four weeks previously. A deceptively simple figure in triple time, repeated first by tenor and bass, leads into a minor theme with Eastern sounding harmonies and rhythm. Muted trumpet and trombone lent further colour to the arrangement.

Last number in the main programme, “Mingus Fingus”, a tribute to the celebrated bass player, is not Charlie Mingus’ own (“pre-Bird”) composition, but a further selection from “Brother Raymond”.

An encore started with a drum solo, leading into the familiar drum intro to Benny Golson’s “Blues March”, recalling Jean Toussaint’s earlier career with the band that made the tune famous. A great ending to a memorable evening!

With appreciation and seasonal wishes for the Progress and Jazz in Reading teams.

Review posted here by kind permission of Clive Downs

Photo by Zoë White Photography

The Steve Fishwick Quintet | November 2018

Friday 23 November, Progress Theatre,, Reading

Steve Fishwick trumpet, Grant Stewart tenor saxophone, John Pearce piano, Jeremy Brown bass, Matt Fishwick drums.

Jazz in Reading scored a mighty coup in securing the appearance on Friday 23 November of New York based tenor saxophone stylist Grant Stewart for his only UK gig outside London and ahead of performances at the BopFest Jazz Festival. Blessed with a huge sound and a slightly laid-back approach reminiscent of his idol Dexter Gordon, Stewart stamped his mark on proceedings from the outset, with front-line partner Steve Fishwick providing a perfect foil with his lightning fast trumpet. The programme bore the hallmark of classic bebop; frenetic, fast-paced, virtuosic and with a competitive edge that kept everyone on their toes – a powerful reminder of the ‘new’ music that took shape in the after-hours sessions of 1940s’ New York, its potent force, enduring influence and a celebration of the creative genius of those who created it.

‘Dance of The Infidels’, an evocative and in these turbulent modern times slightly non-PC title, penned by the brilliant though severely troubled pianist Bud Powell in 1949, established the musical formula for the evening. The brief theme played in unison by the front-line provided the starting blocks for a string of freely improvised solos, resolved by a series of ‘round robin’ exchanges of varying length to bring the performance to a close.

Sounds simple? Don’t be deceived, this is music to challenge the most technically gifted of musicians who would stumble at the first hurdle without a rhythm section of world class quality. John Pearce’s elegant touch at the keyboard combined seamlessly with Jeremy Brown’s beautiful bass lines to keep the music safely on course, while Matt Fishwick’s mercurial drumming, an object lesson in bebop percussion, not only anticipated the route chosen by the principal soloists, but regularly pointed them towards new areas of exploration. Even Steve Fishwick, the epitome of poise and confidence, was moved to express his relief at the conclusion of John Coltrane’s ‘Straight Street’. ‘That was hard,’ he commented.

‘Autumn in New York’, a ballad feature for the tenor saxophone of special guest Grant Stewart brought a change of pace. With the sensitive support of the rhythm he perfectly captured the bitter-sweet sentiments of Vernon Duke’s composition from 1934. I especially loved the way he stretched the notes to hold every drop of emotion and the gorgeous cadenza which brought the tune to a close.

‘Woody n’ You’, was written for bandleader Woody Herman by Dizzy Gillespie in 1942. Though never used by Woody it became a jazz standard nevertheless and in the hands of Messrs. Fishwick and Company it’s not difficult to understand why; its appealing Afro-Cuban rhythms provided a launching platform for some dazzling solos.

The beboppers’ modus operandi of reworking established popular standards by grafting an exotic title and a new, usually much more complex melody, on the original chords served the dual purpose of breathing fresh life into ageing musical war-horses and more importantly, generating a useful source of revenue from royalties. In this way ‘Sweet Georgia Brown’ gave birth to ‘Sweet Clifford’ under the guiding hand of trumpet master Clifford Brown, a number which brought the first set to a truly thunderous climax with a breathtaking drum solo from Matt Fishwick.

Tadd Dameron’s ‘The Scene Is Clean’, memorably recorded by Clifford Brown and Sonny Rollins in 1956, opened the second set. Steve Fishwick and Grant Stewart wove their way around Matt’s atmospheric drum patterns before settling down to a gentle swinger at mid-tempo in which John Pearce’s elegant piano solo was one of many highlights.

‘Little Willie Leaps’ came to life at a 1948 session for Savoy records, which for contractual reasons nominated Miles Davis as leader of what was in reality the Charlie Parker Quintet. Davis provided the four titles, while Parker himself played tenor rather than his familiar alto sax. Unlike the brooding melancholy of so much of Miles’ work, this number is full of joyous expression which set the band into full flight.

Steve Fishwick took centre stage for Victor Young’s timeless classic ‘Stella by Starlight’. A reflective ballad beloved of trumpet and saxophone players alike, Steve demonstrated his remarkable powers of invention and technical assurance aided by the subtle support of his colleagues – the haunting tone of Grant Stewart’s tenor, John Pearce’s ‘moonlight’ touch on the keyboard, Jeremy Brown’s perfectly placed bass notes and Matt Fishwick’s gentle brushwork.

A great evening drew to a close with a bow to the time-honoured jazz tradition of ‘sitting-in’. A whispered aside from Grant to Steve resulted in an invitation to tenor saxophonist Osian Roberts, who ‘just happened’ to be seated in the audience and who ‘just happened’ to have his instrument at hand, to join the band. In a mixture of surprise on his part and the delight of the capacity audience, Osian duly appeared stage-left to contribute an excellent solo to ‘Bouncin’ with Bud’. He remained on stage for an ‘all hands to the deck’ tear-up on ‘Tea for Two’, which closed with another explosive drum work-out by Matt Fishwick.

One notable feature of the gig which could easily have been overlooked and left unreported, was that no amplification and only one microphone, used only for announcements, were in use throughout the evening. In other words, the wonderful quality of the sound, especially the full, rounded tone of Grant Stewart’s saxophone emanated solely from the instruments themselves and the natural acoustic of the Progress auditorium.

We hope that Grant enjoyed his visit to Reading ahead of a full weekend of appearances at the BopFest Jazz Festival and before flying home to the States for a gig in Kansas. As one might say, ‘Reading today. Tomorrow the world!’

As ever, our thanks to everyone at Progress for providing such warm hospitality and for ensuring that every aspect of the evening ran smoothly.

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

Matt Wates Sextet | October 2018

Friday 19 October, Progress Theatre, Reading

Matt Wates alto saxophone, Leon Greening piano, Malcolm Creese bass, Matt Home drums, Steve Main tenor saxophone, Steve Fishwick trumpet & flugelhorn

Having to sit through handful of groan-worthy jokes that easily pre-dated the Relief of Mafeking was a small price to pay for the otherwise sublime pleasure of listening to the Matt Wates’ Sextet at Reading’s Progress Theatre on Friday 19 October. Though the band is brimming with solo talent, it was the quality of Wates’ writing and arranging skills that stood out in my mind throughout the evening. As host-for-the-evening Paul Johnson pointed out in his introduction to the second set, ‘An entire programme of originals can get to be very samey. Not so with Matt Wates.’ With all but two of the tightly-arranged numbers coming from Wates’ prolific pen, each set sparkled with interest, variety and thrilling challenge for musicians and audience alike. He has a remarkable ear for creating melodies that take firm root in the imagination and uses the instrumental resources of the band to bring them to life in full.

The gorgeous bass-lines of Malcolm Creese set the opening number, ‘Victoria’, in motion and introduced the contrasting sounds of the three front-line instruments as they blended together or played their separate parts in developing the theme: the fluid, pure toned and balletic grace of Wates’ alto; the immaculate precision of Steve Fishwick’s trumpet and the dry, muscular tones of Steve Main’s tenor. Leon Greening is both the band’s energy source and harmonic navigator at the keyboard and charts his course with a huge sound. His two-handed, multi-layered approach to soloing never loses sight of the melody and it’s this quality which makes his playing so beguiling. Meanwhile, Matt Home demonstrated the aplomb that makes him the first-call drummer for any situation demanding straight-ahead jazz swing.

‘Heatwave’ maintained the temperature, though at a slightly more relaxed pace, before the band changed into their dancing shoes for the blistering jazz-waltz ‘Hill Street’ – the residents of Hill Street, Reading, located a little more than a mile away from the Progress would have been delighted with this unexpected dedication to their notoriously steep thoroughfare.

‘What Good Is Spring’ brought a change of mood. Composed by Matt Wates’ twin brother Rupert, resident in the United States, it featured the haunting tenor of Steve Main in a beautifully melancholic evocation of spring.

Obviously with a mind to the fast approaching interval and the well-stocked Progress bar, ‘Gin and Bitters’ brought the first set to a suitable close. Bright and cheery, and like the cocktail itself, it held a gentle hint of potential menace.

The second set opened with ‘Third Eye’ and instantly brought to mind the clean, knife-edge swing of Cannonball Adderley’s great bands of the early sixties. ‘We held that together by the skin of our teeth,’ Wates admitted when this breathtaking number came to a close.

‘On the Up’ hit a more funky groove with tenor saxist Steve Main to the fore, while rock inspired ensemble passages added tense excitement to ‘Dark Energy’. The effervescent joy of ‘The People Tree’ culminated in a masterful drum solo by Matt Home.

Steve Fishwick’s mellow flugelhorn set the smoky, blues-soaked scene for ‘After Hours’, a moving dedication to Ray Charles featuring Leon Greening at the height of his keyboard powers.

Matt Wates and Leon Greening presented ‘Beatriz’, a composition by Brazilian guitarist and singer Edu Lobo, as a duo, unleashing in the process a performance of powerfully expressed emotion. Wates’ intense cry of passion was absolutely spellbinding.

Can you think of a better title to describe six young-at-heart jazzers than ‘When We Grow Up’? It wrapped up the evening in suitably playful style, but as no jazz concert is complete without an encore a little persuasion brought the band back to the stage to ride-out the evening with the rousing, ‘Blues for Ari’.

It’s all too easy to take British jazz musicians for granted. The Matt Wates Sextet served to remind us of their world class qualities. As the late alto legend Joe Harriott once observed, ‘Parker? There’s some over here who can play aces too …’

A great evening and thanks as ever to the Progress ‘House Team’ for the warmth of their hospitality and flawless management of sound and lighting.

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

Elftet | September 2018

Friday 28 September, Progress Theatre, Reading

Jonny Mansfield vibes & leader, James Davison trumpet & flugelhorn, Rory Ingham trombone, Tom Smith alto saxophone, Sam Rapley tenor saxophone & bass clarinet, Dom Ingham violin & vocals, Ella Hohnen Ford vocals & flute, Laura Armstrong cello, Oliver Mason guitar, Will Harris bass guitar, Boz Martin-Jones drums.

We can’t say that we weren’t warned. Just a few weeks ago Jonny Mansfield, appearing with Jam Experiment, accepted an invitation to join Jazz in Reading’s Bob Draper on the Progress stage for a brief interview to promote his forthcoming Elftet concert. ‘Why an Elftet?’ asked an incredulous Bob. ‘An eleven-piece band!’ ‘It gives me the chance to write for a broad musical palette and to create colours and textures beyond what’s possible in a small group,’ replied Mansfield.

And how! Jonny’s self-effacing response gave no hint of the immense power that eleven musicians, at the top of their game on the penultimate night of a thirteen-gig national tour, can generate. To say we were blown away is an under-statement. It’s certainly no exaggeration to say that those privileged to be in the audience bore witness to the arrival of a major new instrumental and writing talent on the jazz scene. ‘It was like a breath of fresh air,’ remarked one stalwart of Jazz at Progress. For others, this writer included, it prompted memories of Messrs. Gibbs, Garrick and Westbrook in the nineteen-sixties and the later glories of Kenny Wheeler and Loose Tubes; bands which broke the established mould and added a new dimension to ensemble jazz.

Even in this day and age of heightened awareness of gender inequality, the jazz world is still dominated by all-male groups, where a female vocalist may be the only acknowledgement of women’s contribution to this area of music. Here, it was wonderfully refreshing to see two women, Ella Hohnen Ford and Laura Armstrong, absolutely intrinsic to the band line-up, performing as equal members of the ensemble and its improvising soloists, both of whose individual qualities added superbly to the unique sound of Elftet.

Mansfield may never have stepped into a sailing boat, as he admitted in his introduction to ‘Sailing’, but his impression of what he thought it might be like was the most perfect evocation of the experience that I can imagine. The blasts of Rory Ingham’s declamatory trombone launched the piece into motion. Alert to the challenges and ever-changing rhythms of wind and tide depicted by Mansfield’s arrangement, Ella Hohnen Ford, her wordless vocal blending beautifully with Dom Ingham’s violin, held a firm grasp on the tiller and brought the boat safely home. One couldn’t fail to be impressed by the startling originality of Mansfield’s writing, played with the spirit and gusto of a New Orleans street band, and the subtlety of the instrumental voicings. As he commented in his interview with Bob Draper, ‘Writing a tune is straightforward. Making it work for the ensemble takes a lot longer.’

Mansfield’s ear for putting together an interesting programme was fully in evidence in the next two numbers played back-to-back. ‘Falling’, a gentle lullaby inspired by ‘Golden Slumbers’ a poem by Thomas Dekker, contrasted brilliantly with ‘For You’, an almost pastoral piece, featuring the dazzling inventiveness of James Davison, winner of this year’s Musicians’ Company Young Musician Competition* on flugelhorn and the featherlight alto saxophone of Tom Smith. It finished with some stunning Gospel-like chords.

Sadly, ladybird’s are now rare visitors to my garden. Mansfield’s next piece, ‘Wings’, an interpretation of the traditional nursery rhyme ‘Burnie Bee’, used his vibes in a gorgeous combination with Ella Hohnen Ford’s voice, the violin of Dom Ingham, Laura Armstrong’s cello and Sam Rapley’s bass clarinet to capture the exquisite beauty of this well-loved creature. But there is a darker aspect to this seemingly benign beetle, as Mansfield made clear in a vibes solo of growing intensity; it can exude a pungent fluid to ward off its enemies – ants, birds … people!

‘Flying Kites’ completed the first set. As with earlier pieces, Mansfield used the full resources of the ensemble, in this instance to create a vivid image of the joys and frustrations of flying a kite. The bass guitar of Will Harris anchored the kite firmly to the ground, while each player in turn helped to launch it into the sky; fantastic guitar from Oliver Mason, whose playing was a constant delight throughout the evening, pizzicato violin from Dom Ingham and a show-stopping drum solo from Boz Martin-Jones.

The second set opened with the thoughtfully reflective ‘Silhouette’, which amongst many delights featured a wonderfully free-form vibes solo by the leader with the rhythm section in support, the resonant tones of Sam Rapley’s bass clarinet and a ripping alto solo by Tom Smith.

Mansfield crowned the evening with ‘Tim Smoth’s Big Day Out’. This imaginative and extraordinarily ambitious suite, lasting a full forty-five minutes, featured the ensemble members as soloists or in a variety of instrumental groupings that fully expressed the poetic qualities of Mansfield’s writing. The repetition of a seemingly simple vocal line, from which Ford drew scope for endless variations, linked the respective parts together. One was almost overawed by the emotional maturity and technical brilliance of each player and their determination to push the music to the utmost limits. Tom Smith’s (Yes, the play-on-words of the title scarcely disguises that this piece was written specifically for him as a tribute to his constant inspiration as a musician who always ‘questions what is possible’) unaccompanied alto solo, modelled on the work of American saxophone virtuoso Colin Stetson, held the audience spellbound as he extracted sounds from his instrument that no one could have imagined previously existed.

‘Present’, was written for fellow vibes player Jim Hart after he recommended that Mansfield read Eckhart Tolle’s ‘The Power of Now’. It brought the concert to rip-roaring close.

Jonny Mansfield is a worthy recipient of the 2018 Kenny Wheeler Jazz Prize awarded to a graduating musician at the Royal Academy of Music who demonstrates excellence in performance and composition. This has led to a recording opportunity, which features Elftet with special guests, Chris Potter on saxophone, Kit Downes on Hammond organ and Gareth Lockrane on flute. The album will be released on Edition Records early next year.

On Saturday 13th October he will be leading Elftet at the Marsden Jazz Festival with the presentation of ‘On Marsden Moor’, a specially commissioned suite that combines the instrumental ensemble with song and spoken word. This will be recorded by BBC Radio 3 and broadcast at 11pm on Monday 12th November.

As ever, our thanks to the Progress Theatre ‘house-team’ for their hospitality and the excellent quality of the sound and lighting.

I should like to round-off this review with the following comment; written by Marc Edwards, a gentleman who works tirelessly to promote emerging-jazz talent in the UK, but I feel sure, shared by many:

‘A fabulous night at Progress. With players, bandleaders and composers of this calibre, the future of new music, powered by such a breadth of influences is bright.’

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

* Other finalists in this competition included saxophonist Alex Hitchcock, and bassist Joe Downard, both of whom will be familiar to Progress audiences.

Jam Experiment | August 2018

Friday 31 August, Progress Theatre, Reading

Rory Ingham trombone, Dominic Ingham violin & voice, Toby Comeau keyboard, Joe Lee bass, Jonny Mansfield drums

Hot foot from a marathon recording session in Wales and a triumphant European tour taking in Berlin, Warsaw, Kracow and other points East, Jam Experiment took to the stage of the Progress Theatre in ebullient spirits on Friday 31 to open a new season of Jazz at Progress. Formed four years ago, the band has already notched up huge critical acclaim from its numerous club appearances at such venues as Ronnie Scott’s and the Vortex , the stages of the London and Cheltenham Jazz Festivals, its radio broadcasts for Radio 3 and Jazz FM and inaugural CD, Jam Experiment.

The band is fronted by the irrepressible Rory Ingham, winner of the Rising Star Award in the 2017 British Jazz Awards. He commands a trombone chair in both NYJO, with whom he played at this year’s Proms in an ambitious programme devoted to the music of George Gershwin, Stan Kenton and Laura Jurd, and the Syd Lawrence Orchestra. It came as no surprise to learn that he cites Peter Kay as being high on his list of comedy heroes.

Dominic Ingham, dead-pan-faced Laurel to his more ebullient brother’s Oliver Hardy, completes the front-line on violin and voice, his ear finely tuned from early childhood training in the Suzuki method of playing. Toby Comeau whose background included an enriching experience as a chorister at Truro Cathedral before an attraction to jazz took root, plays keyboard. He is joined in the rhythm section by Joe Lee, a fellow chorister at Truro, whom Toby inspired to take up bass. Jonny Mansfield completes the line-up on drums; vibraphonist with NYJO and the 2018 recipient of the prestigious Kenny Wheeler Jazz Prize awarded to a ‘graduating musician at the Royal Academy of Music who demonstrates excellence in performance and composition’.

This stellar line-up of emerging jazz talent, each a product of either the Royal Academy of Music or Guildhall School of Music, and with an average age of about 21, clearly take their music seriously. That they are equally determined to have a ball creating it and sharing their sense of fun and musical adventure with the audience, became immediately obvious with the opening bars of ‘Richie’s Scalp’, a ‘raising-of-the hairs-on-the-back-of-the neck’ sensation induced by Rory Ingham’s soulfully declamatory trombone. What an opening number! Dominic’s amplified violin matched the trombone for volume but took the theme into more linear territory; eerie swirling lines fueled by the funky rhythm section.

Quite how Quay – the ‘Sunnies with Melbourne flair’ – inspired Joe Lee to write a tune of that title is perhaps best left unexplained. No matter. A beautifully evocative violin solo blossomed from the composer’s fulsome bass line, with trombone, keyboard and drums adding their respective musical colours to the soundscape.

‘Theaker’s Barn’, drew yet another gem from the Jam Experiment’s box of delights with Dominic Ingham taking an instrumental line with his appealingly light and airy voice; the sort of thing at which Norma Winstone excels. It blended perfectly with the mellow tones of Rory’s trombone and the intricate backgrounds conjured by Messrs Comeau, Lee and Mansfield. Can you think of any other male performers who use their voice in this way? Answers on a postcard to Jazz in Reading please.

Toby Comeau further demonstrated the writing strengths of the band members with a beautiful sound portrait of ‘Appledore’, the West Country town famed for the quality of its shipbuilding, while Jonny Mansfield’s hypnotic ‘Ichi Ni’ (one, two, three in Japanese and a neat play on words – ‘Itchy Knee’. Get it?) brought the first set to a close.

The resounding clatter of the end-of-interval bell summoned the faithful from the liquid attractions of the bar and back to the Progress auditorium, where MC for the evening Bob Draper held centre-stage in the company of Jonny Mansfield. What better way of publicizing the next Progress gig than an interview with the protagonist himself. This promises to be an intriguing event; an eleven-piece band – Elftet – including strings, giving full rein to what no less a jazz authority than Alyn Shipton has described as ‘strikingly original music’. Friday 28 September is a date to place in the diary!

The conversational style of Mansfield’s writing shone through ‘BMTC’, the opening number of the second set. As if to say, ‘Hey guys, let’s see where this will take us’, ideas bounced about freely giving the arrangement a wonderful sense of spontaneity and providing a perfect launching pad for Mansfield’s superlative workout on drums.

I can only describe ‘Tin’, the third of Mansfield’s compositions, as a gorgeous multi-layered tapestry of sound, bearing the indelible thread of Dominic Ingham’s voice and Toby Comeau’s keyboard extemporization.

Dominic Ingham’s ‘Hop the Hip Replacement’ hit an altogether brighter groove, as the tongue-twisting title implies, while ‘Bonsai’, with the simplicity of its lyric and compelling bassline, should take its place as a modern-day lullaby.

‘Get It On Target’, featuring a dazzling solo by Toby Comeau and a final effort by Rory Ingham to lift the roof may have brought the evening to its ‘official’ close but there was no way that Jam Experiment could leave the stage without an encore. They duly obliged and only then did the audience reluctantly accept that the gig had come to an end and that they would have to make their way home.

In a process of musical alchemy Jam Experiment have blended their individual talents within the proverbial jazz melting pot with a good measure of contemporary influences and the addition of a fistful of Yorkshire grit. When left to cool in the fresh breezes of the English West Country the result is an amalgam of pure musical gold. Catch the band when you can!

Thanks are due to the Progress team for their warm hospitality, efficient service and the high quality of the sound and lighting, and Marc Edwards of ‘Brecon Jazz Futures’ for his instrumental role in bringing Jam Experiment to the Progress Theatre.

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

The Reading Dusseldorf Jazz Ensemble | July 2018

Reading Fringe Festival Main Stage, Reading Station Hill Plaza, Wednesday 25 July

Stuart Henderson (trumpet & flugelhorn), Reiner Witzel (alto saxophone), Pete Billington (keyboards), Raph Mizraki (bass & electric bass), Simon Price (drums).

‘How long have the band been together?’ I was asked by one of several curious bystanders who were drawn to the Main Stage of the Reading Fringe Festival as the sound of five jazz musicians in rehearsal drifted Pied Piper-like across Reading Station Plaza early on Wednesday evening. ‘About two hours,’ I replied. ‘Two hours!’ he gasped. ‘That’s amazing. What is it about jazz that guys can get-it-together like that?’

With that, he continued on his way in puzzled amazement, promising that he would try to return for the concert at the appointed time.

In truth I hadn’t been entirely honest with my response. Four of the musicians play regularly under the leadership of Stuart Henderson and are well known to local jazzers as the Stuart Henderson Quartet. But, alto saxophonist Reiner Witzel had only flown into Heathrow from Dusseldorf a few hours earlier, giving him just enough time to meet the guys at Stuart’s home, and to check into his Friar Street Hotel, before making the sound-check and rehearsal at the Main Stage.

And to explain the background to this unique occasion a little further; Stuart had played as a guest with Reiner’s Dusseldorf Jazz Ensemble in Dusseldorf on 30th June, in a hugely successful concert which also featured guest soloists from Haifa and Chemnitz – each guest representing a community with which Dusseldorf is twinned. Reiner’s appearance in Reading, which he first visited thirty years ago as a youthful member of a big band, reciprocated that event to forge an additional link of friendship between Reading and Dusseldorf.

In the circumstances the musicians could easily have settled for a programme of well-worn standards familiar to themselves and the audience. But no, this was a special occasion, not just in terms of the link between Reading and Dusseldorf, but as an opportunity to showcase the original writing talents of Stuart and Reiner and to present jazz at its best and most challenging as part of Reading Fringe Festival. They hit the groove with the opening number, Reiner Witzel’s ‘Northern Fields’, and during the course of three sets held the near capacity audience spellbound with music of truly world class quality.

The contrast between the protagonist’s writing styles made for fascinating listening. Witzel sometimes dark and brooding, captured the pulse of life in a Charlie Mingus-like fashion of startling sounds and shifting times and rhythms with the brilliantly evocative ‘Tales of a Century’, ‘Nomansland’ and ‘Hafenhunde‘ (The Dogs of The Port)

Henderson, on the other hand revealed a much lighter touch with debut outings for three very lyrical pieces. His arrangement of ‘Sumer Is i-cumen in’, written down by a monk in Reading Abbey in about 1240, said to be ‘the earliest existing example of harmonized secular music’ and indelibly inscribed in the primary-school-day memories of generations of Reading children, was a pure delight – a medieval four-part round in jazz bossa-nova style – and a fitting tribute to the recent re-opening of Reading Abbey. ‘Reflections’, featuring the gorgeous piano of Pete Billington, was the sort of wistfully romantic ballad that sadly nobody seems to write any more – except thankfully Stuart Henderson. ‘Three Rivers’ beautifully captured the flow and various moods of Reading’s principal rivers, the Thames, Kennet and Holy Brook.

‘Voyage’ and ‘Gibraltar’, two post-1960 classics from respectively Kenny Barron and Freddie Hubbard, gave everyone free-rein to exercise their ‘jazz-chops’. Fiery alto from Witzel, blistering trumpet runs from Henderson, who revived the lost art of growling plunger mute to outstanding effect, and understated swing from Billington. Alert to every shift in gear Raph Mizraki’s rich-toned bass held the rhythm section firmly in place in partnership with the explosive drumming of Simon Price.

In an evening rich with surprises, none more so than the inclusion of two numbers from Miles Davis ‘electric’ repertoire, ‘Tutu’ and ‘Shh Peaceful/It’s About That Time’. Though Miles’ innovations with electronic instruments in the late-1960s and onwards divided fans and critics alike, they had a lasting influence on jazz, giving birth to the entirely new genre of ‘jazz fusion’. I can still vividly remember the spine-tingling experience of listening to ‘In A Silent Way’ on its release in 1970. And yet, to my knowledge, unlike titles such as ‘So What’ or ‘Walkin’’ from earlier albums, nobody actually plays anything from the ‘electric’ bands.

Why not? Of course, at the time we didn’t know, and could never had imagined, that ‘In A Silent Way’ was painstakingly created in the editor’s cutting room from hours and hours of tape, while ‘Tutu’ took the innovation a stage further and Miles played over the lush pre-recorded arrangements of Marcus Miller. Playing the tunes ‘live’ naturally presents quite a challenge, but not one to be missed by the Reading Dusseldorf Jazz Ensemble!

The results were outstanding. The band drew on its entire bank of sound resources to deliver each piece; Witzel’s haunting alto, and Henderson’s sparse trumpet interjections, overlaying the kaleidoscopic background of Mizraki’s slap bass, the celestial effects conjured from Pete Billington’s keyboard, and the hypnotic beat of Simon Price’s drums. The band not only remained faithful to the original feel of the albums, we had the bonus of the spontaneity which only comes in a ‘live’ performance.

‘Swagmeister’, a dedication to Stuart’s son who informed his father about the word ‘swag’ to be the ultimate in cool, brought a fantastic evening to a swinging close, and the audience to its feet in rapturous appreciation. As one happy punter commented, ‘I’ve listened to jazz in New York and all over the world. This ranks with the best I’ve ever heard!’ Here, here!

The Reading Fringe Festival Main Stage, a remarkable structure of inflated plastic seemed to hold the ominous promise of a weight-reducing sauna at the beginning of the evening. To everyone’s surprise it proved to be perfect for the performance, with an atmosphere of its own that grew as the evening progressed – the next best thing to playing outdoors on a beautiful mid-summer’s evening. Sound and Lighting were handled magnificently by the resident Technical Team, while the Front of House Team engendered the welcoming and ‘can’t-do-enough-for-you’ spirit of Reading Fringe Festival.

Thanks are due to the Reading Dusseldorf Association for their support and to Paul Johnson of ‘Jazz in Reading’ who ensured that all the strands of organization were firmly drawn together to make the event possible.

Reiner Witzel took his flight back to Germany early on Thursday morning in advance of working on a cruise departing from Hamburg later in the day – such is the schedule of an internationally based musician. Stuart Henderson & Company can be seen at their resident spot at the Retreat on the last Sunday of each month – don’t miss the opportunity to see them in action.

Can we look forward to a further episode in the jazz-link between Reading and Dusseldorf and further involvement with Reading Fringe Festival? The interest and goodwill are certainly there, so why not!

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

Rebecca Poole Quintet | May 2018

Progress Theatre, Reading Friday 25 May

Rebecca Poole Quintet: Rebecca Poole vocals, Brandon Allen tenor sax, Hugh Turner guitar, Raph Mizraki bass, Steve Wyndham drums

What better way to round-off another successful season of jazz at Reading’s Progress Theatre than in the company of Rebecca Poole and her quintet on Friday 25 May. Any date with Henley-based Rebecca, AKA Purdy, is guaranteed to set faces smiling, heads swaying and feet tapping, and she didn’t disappoint the near sell-out audience, adding many new fans to her legion of admirers. Multiple award-winning Brandon Allen on tenor saxophone and Hugh Turner on guitar, added their solo voices to the occasion, and demonstrated the subtle art of vocal accompaniment to perfection, with the reliable and ever-swinging support of Raph Mizraki and Steve Wyndham.

Rebecca’s warmth and fun-filled personality illuminates the stage while the broad expanse of her vocal canvas covers songs of lasting appeal together with originals with a more contemporary feel. Evergreen standards like ‘I Can’t Give You Anything but Love’ and ‘Bye Bye Blackbird’, dating back to the 1920s, comfortably rub shoulders with numbers she has recorded under her alter ego as Purdy, like ‘Too Much in Love with Love’, ‘Look into Your Mirror’ or the charmingly wistful ‘Cherry Tree’.

She handled the pacey vocal gymnastics of ‘Love Me or Leave Me’ with consummate ease, and knowingly drew every ounce of innuendo from the lyrics of ‘Put the Blame on Mame’, a lady whose ribald behavior caused the San Francisco earthquake amongst a string of other natural disasters. But Rebecca’s voice also has an intimate ‘late-night’ quality, perfectly suited to expressing the bitter grains of ‘Black Coffee’, as well as the seductive promise of ‘Perhaps, Perhaps, Perhaps’, hit songs for two of her strongest influences, Peggy Lee and Doris Day.

‘I Can’t Wait to Meet You’, another original, featured Rebecca in an enjoyable duet with guitarist and MD Hugh Turner. It ended with an ‘Oh Yeah’ that almost out-graveled Satchmo himself!

Star tenor saxophonist Brandon Allen blew a storm on his four instrumental features: the bebop classic ‘Good Bait’, ‘No More Blues’ a delightful Latin American number by Antonio Carlos Jobim,

‘Caravan’ and Jimmy Van Heusen’s wonderful ballad ‘But Beautiful’. He was ably assisted by the outstanding Hugh Turner on guitar, who can summon every sound imaginable from his instrument; the lightest Latin-American touch to the heaviest blues-soaked riff, the walking bass of Raph Mizraki and the rhythmic pulse of Steve Wyndham’s drums.

As the show drew to a close, the band laid down an earthy beat, Rebecca belted out the verse, and the audience at last gave vent to emotions held in check throughout the evening and joined in with the chorus to what else but, ‘Minnie the Moocher’. Top that as they say. And she did with the encore. ‘Just a Gigolo’, with the interpolation of ‘I Ain’t Got Nobody’, had everyone singing their heads off!

As ever very many thanks to the team at the Progress Theatre for hosting the jazz programme organized by Jazz in Reading and we look forward to the new season which commences in August.

Meanwhile, local trumpet hero Stuart Henderson will be appearing at the Reading Fringe Festival on Wednesday 25 July with the Reading Dusseldorf Jazz Ensemble featuring special guest Reiner Witzel. Full details are available on www.jazzinreading.com

Review posted here by kind permission of Trevor Bannister.

Photo by Zoë White Photography

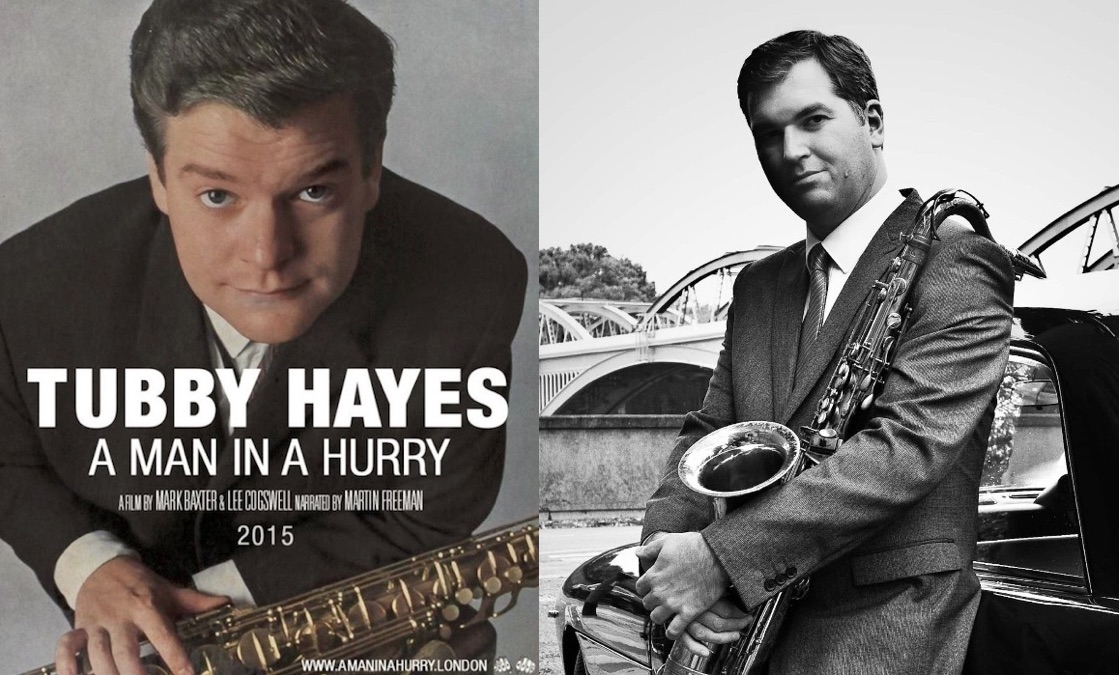

Tubby Hayes: A Man in a Hurry | Jazz and film evening at the University of Reading | May 2018

University of Reading, Friday 11 May 2018

Top: John Horler, Alec Dankworth, Simon Spillett, and Spike Wells

Bottom: Simon Spillett and Mark Baxter

A night of Jazz and Film to celebrate Tubby Hayes with the Simon Spillett Quartet and the acclaimed film documentary ‘Tubby Hayes: A Man in a Hurry’

The young boy stood with his father and gazed in wonder at the gleaming family of three saxophones displayed in the window of the music shop local to his home in south London. He pointed to the middle-sized instrument, a tenor saxophone, and announced, ‘That is what I want to play’.

His father, a professional dance musician himself, agreed to the request but added the caveat that as his son was already learning to play the piano and violin he would have to wait until his twelfth birthday. True to his word he handed the instrument to his son on the due date and so, began the legend of Edward Brian ‘Tubby’ Hayes.

On Friday 11th May, Jazz in Reading, in collaboration with Music at Reading, celebrated the music and life of Tubby Hayes in the lovely setting of the University of Reading London Road Campus, with live jazz from the Simon Spillett Quartet followed by Mark Baxter’s remarkable documentary film ‘Tubby Hayes: A Man in a Hurry’; a format guaranteed to ensure that the flame of Tubby’s spirit and musical legacy continues to shine brightly.

On Friday 11th May, Jazz in Reading, in collaboration with Music at Reading, celebrated the music and life of Tubby Hayes in the lovely setting of the University of Reading London Road Campus, with live jazz from the Simon Spillett Quartet followed by Mark Baxter’s remarkable documentary film ‘Tubby Hayes: A Man in a Hurry’; a format guaranteed to ensure that the flame of Tubby’s spirit and musical legacy continues to shine brightly.

Born on 30th January 1935, and a professional musician by the age of fifteen, ‘Tubby’ Hayes is arguably the most complete jazz musician ever to emerge from these shores. His tragically brief career ended on Friday 8th June 1973 when he died following heart surgery. He was thirty-eight years old.

The five carefully selected numbers by the Simon Spillett Quartet cast their own distinctive light on Hayes’ career. ‘Royal Ascot’, an early Hayes composition dedicated to the horse-racing proclivities of Ronnie Scott, opened the evening with the authoritative tenor sound and breakneck tempo that used to cast fear into rhythm sections whenever he played at provincial jazz clubs.

No such hesitancy here. Spillett’s quartet, world-class musicians all, handled the challenge with consummate ease. And no wonder. Pianist John Horler and drummer Spike Wells each played with Tubby in their early careers; Wells as a regular member of both Tubby’s quartet and big band in the late-1960s. Alec Dankworth, a brilliant bassist, is linked to Hayes via the association between Tubby and his father, the late Sir John Dankworth.

‘The Serpent’, another dedication, this time to Bix Curtis, a promoter and MC with whom Tubby toured with ‘Jazz in London’ in 1956, captured the barn-storming days of the Jazz Couriers, the band Hayes co-led with Ronnie Scott between 1957 and 1959. By this time Tubby’s reputation had found its way to the States where musicians were beginning to sit up and take notice of the young ‘upstart’ from Britain. In 1961 he was invited to play at New York’s famous Half Note Club. He also recorded with Clark Terry and an American rhythm section. Spillett’s interpretation of the gorgeously bluesy ‘A Pint of Bitter’, the best-known number from that session, bore the distinctive imprint of its composer Clark Terry and served as an effective reminder of how Hayes could stretch-out at medium-tempo.

Hayes was a great ballad player and Spillett expressed the lyrical beauty of ‘Souriya’ to perfection, with an exquisite solo from John Horler and sensitive support from Dankworth and Wells. ‘Off the Wagon’ brought the set to a close. A highlight track on Tubby’s landmark album ‘Mexican Green’, and once described as representing ‘the strength, vitality and invention of Tubbs at his best’, it featured a brilliantly conceived and perfectly executed drum solo from Spike Wells

The generous applause which followed spoke volumes for the appreciation of the audience. Simon Spillett remained on hand to introduce ‘Tubby Hayes: A Man in a Hurry’. This remarkable documentary film, produced by Mark Baxter, directed by Lee Cogswell and released in 2015 to coincide with the eightieth anniversary of Tubby’s birth, catches the energetic force of Hayes’ personality and as the title implies, the relentless pace of his career. Narrated by Hayes devotee Martin Freeman it charts Tubby’s life and times through interviews, archive photographs and rare movie footage. He lived enough during his thirty-eight years to fill several lifetimes. That such a life style extracted its inevitable toll is more than evident in the stark contrast between the buoyant, ever-smiling persona of Tubby in his heyday, and the harrowing, almost unrecognizable shots of him awaiting a court judgement following a drugs’ bust towards the end of his life.

Baxter and his production team avoided the temptation to either over-eulogise Tubby’s life or to portray him as the victim of an unsympathetic society. Nevertheless, the film leaves no doubt whatsoever that his arrest and subsequent conviction in 1968 for possession of diamorphine, incurring a fine of £50 with costs of £5.5s, tells us as much about the publicity seeking zeal of the notorious Det/S Norman “Nobby” Pilcher of Scotland Yard as Tubby’s wayward habits. Tubby, I feel sure, took responsibility for his own destiny, and the film holds faith with that honesty.

At times the film has the comforting feel of a long-forgotten family photograph album opening-up a world otherwise lost for ever; the percussionist humping an enormous kettle drum on his back as he joined the crowded open-air musicians’ labour-exchange on a Monday morning in Archer Street; the dowdy interior of Ronnie Scott’s original club in Gerrard Street and scores and scores of sharply dressed musicians, their hair stylishly cut and held in place by oodles of Brylcreem. Until prompted by an observation in the film I had never considered the sartorial elegance of modern jazz musicians in the 1950s and 60s, but as several interviewees testified, ‘looking the part’ was an essential part of the jazz scene and indeed gave birth to the ‘mod’ culture we associate with images of ‘Swinging London’. Not everyone could play like Tubby Hayes, but anyone could live the dream and dress like him!

Mouth-watering extracts from Tubby’s big band broadcasts for BBC 2’s ‘Jazz 625’ and appearances as a featured artist on TV spectaculars with the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Henry Mancini, reminded us that Tubby was a well-known personality within the mainstream of entertainment. His on-screen film credits include the Hammer classic ‘Dr Terror’s House of Horrors’, and it’s Tubby’s tenor which adds mounting tension to the closing scenes of ‘The Italian Job’.

An inevitable weakness of the film is that so few of Tubby’s contemporaries are still with us. Fascinating as they are, most of the ‘talking heads’ were drawn from a younger generation, like the producer Mark Baxter, who discovered Tubby via his recordings. This makes the contributions of those from who knew Tubby personally, like poet Michael Horowtiz and fellow musicians Spike Wells and Cliff Hardie doubly valuable. None more so than Tubby’s eldest son Richard. He described his father as having a rather vague and distant place in his life. ‘I didn’t have time to be a father’, Tubby confessed in a brief but telling interview clip.